I will assume the reader has some basic knowledge of differential geometry including the standard notions of a connection.

Connections on (or in) fibre bundles are confusing things when you first meet them. They maybe introduced as a way of defining parallel transport of objects along curves, for the tangent bundle you may have been introduced to them as directional derivatives and so on. A rather general notion is that put forward by Ehresmann as the compliment to the vertical bundle which we call the horizontal bundle. Note that Ehresmann’s defintion works for any fibre bundle and not just vector bundles. Even more abstractly we can define a connection on a fibred manifold as a section of its first jet bundle.

Okay, so we all agree that are confusing things. However, for vector bundles we can describe them completely geometrically as certain maps between double vector bundle. For double vector bundles see for example [1]

Double vector bundles

I won’t describe general double vector bundles here, all we really need is the tangent bundle of a vector bundle \(TE \), which we equip with natural local coordinates \((x^{A}, y^{a}, \dot{x}^{A}, \dot{y}^{a}) \). The coordinate transformations here are given by

\(x^{A’} = x^{A’}(x)\)

\(y^{a’} = y^{b}T_{b}^{\:\: a’}(x)\)

\(\dot{x}^{A’} = \dot{x}^{B}\frac{\partial x^{A’}}{\partial x^{B}}(x)\)

\(\dot{y}^{a’} = \dot{y}^{b}T_{b}^{\:\: a’}(x) + y^{b}\dot{x}^{B}\frac{\partial T_{b}^{\:\:a’}}{\partial x^{B}}(x)\)

It is now convenient to view this double vector bundle as a bi-graded manifold by assigning a bi-weight as \(w(x) = (0,0)\), \(w(y) = (1,0)\), \(w(\dot{x}) = (0,1)\) and \(w(\dot{y}) = (1,1)\).

Note that as a graded manifold the coordinate transformations must respect this bi-grading. A quick look at the transformation laws show that they do preserve this bi-grading. In fact, under some mild conditions, we can always view a double vector bundle as such a bi-graded manifold. This is far more convenient than the original definitions as a vector bundle in the category of vector bundles, where one has to check all the compatibility conditions.

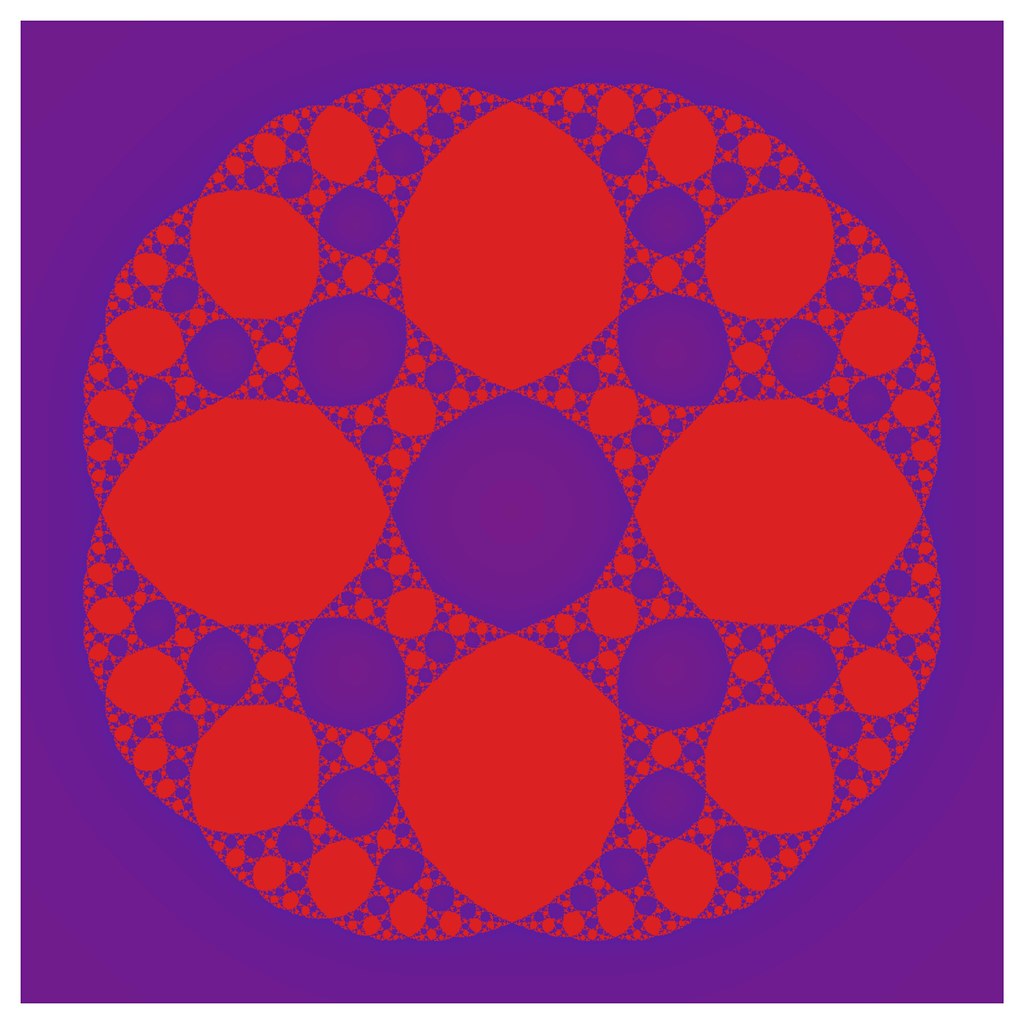

We have the following vector bundle structures

The core of this double vector bundle is identified with \(ker(T\pi)\) which is the vertical bundle \(VE\), which you can easily see is isomorphic to \(E\).

As we have a bi-graded structure here we can also pass to a graded structure by considering the total weight. That is just sum the components of the bi-weight. In doing so we get what is know as a graded bundle of degree two [2]. In simpler language we have the series of fibrations

\(TE \rightarrow E \times_{M} TM \rightarrow M \),

defined by first projecting out \(\dot{y}\), which has weight 2 and the then projecting out \(y\) and \(\dot{x}\) which have weight 1. Again you can see that this is all consistent with the coordinate transformations.

Also note that \(E \times TM\) also carries the structure of a double vector bundle simply by projection onto the two factors and then the obvious projections to \(M\). This can be viewed keeping the bi-weight as inherited by that on \(TE \).

Connection in a vector bundle

Now let me define in a non-standard way a linear connection.

Def A (linear) connection on a vector bundle \(E\) is a morphisms of double vector bundles (bi-graded manifolds)

\(\Gamma: E \times_{M}TM \rightarrow TE\),

that acts as the identity on the vector bundles \(E\) and \(TM\).

So, does this reproduce the more standard definitions? Let us look at this in local coordinates;

\((x^{A}, y^{a}, \dot{x}^{A}, \dot{y}^{a})\circ \Gamma = (x^{A}, y^{a}, \dot{x}^{A}, \dot{x}^{A} y^{b} (\Gamma_{b}^{\:\: a})_{A}(x))\).

The question now is how do the components of the morphisms \((\Gamma_{b}^{\:\: a})_{A}\) transform under changes of local coordinates?

It is not hard to see that we have

\((\Gamma_{b’}^{\:\: a’})_{A’} = \frac{\partial x^{B}}{\partial x^{A’}}\left(T_{b’}^{\:\: c} (\Gamma_{c}^{\:\: d})_{B}T_{d}^{\:\: a’} + T_{b’}^{\:\: c} \frac{\partial T_{c}^{\:\: a’}}{\partial x^{B}} \right)\),

thus the local data of a linear connection as I defined it coincides exactly with the local data of the connection coefficients of connection on a vector as defined in any textbook on differential geometry.

Acknowledgements

I won’t claim originality here, this understanding was largely inspired by a lecture given by Prof. Urbanski.

References

[1] Kirill C. H. Mackenzie, “General Theory of Lie Groupoids and Lie Algebroids”, Cambridge University Press, 2005.

[2] J. Grabowski and M. Rotkiewicz, Graded bundles and homogeneity structures, J. Geom. Phys. 62 (2012), no. 1, 21-36.