|

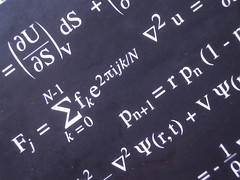

The subject of a quantum theory of gravity is interesting, technical and very difficult. However, there are three basic principles that we expect such a theory to obey. |

Creating a full quantum theory of gravity seems to be out of our reach right now. String theory comes close, but the full theory here is not understood. Loop quantum gravity also offers a good picture, but again technicalities spoil achieving the goal.

I am no expert in quantum gravity, but I thought it maybe interesting to outline three basic ‘rules’. The full quantum theory of gravity should be:

- Renormalisable (maybe not perturbatively) or finite.

- Background independent.

- Reducible to general relativity (plus small corrections) in a sensible classical limit.

As a warning, I will not be too technical here, but will use some standard language from quantum field theory.

Renormalisable

The standard methods of quantum field theory are to expand the theory about some fixed configuration, usually the vacuum, and consider small fluctuations about this reference configuration. However, in doing so some techniques are needed to remove the appearance of infinite values of things you would like to measure in the lab. These methods are collective known as ‘perturbative renormalisation’. For example, we know that the quantum theory of electrodynamics can be handled properly using these methods.

However, general relativity as described by Einstein is not amenable to methods of perturbative renormalisation. Well, this is true if we want a full theory. What one can do is consider quantum general relativity as an effective theory. That is we accept that at some energy scale the theory will breakdown, but as long as we are not at that scale the theory is okay. By adding a ‘cut-off’ we can understand quantum general relativity using Feynman diagrams to ‘one-loop’ and calculate graviton scattering amplitudes and so on.

Interestingly, there is some evidence that general relativity or something close to it is nonperturbatively renormalisable; this is known as asymptotic safety. With no details, the idea is that quantum general relativity is not ‘sick’ and well-defined, just not as a perturbative theory like quantum electrodynamics. This is fascinating as it means that a proper quantum theory of gravity may not be a theory of gravitons after all! Recall that small ripples in the electromagnetic field are quantised and understood to be photons. Maybe it is not really possible to describe quantum gravity in a similar way where small ripples in space-time are quantised.

Alternatively, a full theory of quantum gravity could be finite. That is we can employ perturbative methods, but do not need renormalisation techniques. Amazingly, we know of supersymmetric Yang-Mills theories that are finite. Moreover, superstring theory is also finite (I am unsure as to how rigours the proof are here, but the string community generally accept this as fact). It maybe possible that the full theory of quantum gravity is finite from the start. This suggests that looking at supersymmetric theories of gravity is a good idea, but by no means the only thing one can think about.

In short, any full quantum theory of gravity must allow us to calculate things we can hope to measure.

Background independence

This means that the theory should not depend on any chosen background geometric fields. In particular, this is taken to mean that the theory should not require some chosen background metric.

String theory as it stands fails on this. However, string theory is usually employed using perturbation theory and so some classical background is chosen, often 10-d flat space-time.

Loop quantum gravity seems better in this respect, but it has other problems.

In short, any full quantum theory of gravity should not require us to fix the geometry (and maybe topology) from the start.

Reduce to general relativity

General relativity has been so successful in describing classical gravitational phenomena. It is tested to some huge degree of accuracy and so far no deviations from it’s predictions have been found. General relativity is a good theory within the expected domains of validity.

Thus, any quantum theory of gravity must in some classical limit reduce to general relativity, up to small corrections. These quantum corrections must be small enough as not to be seen already in astrophysics and cosmology.

If a quantum theory of gravity cannot be shown to reduce to general relativity in some limits (there maybe several ways of doing this) then we cannot be sure that we really have a quantum theory of gravity.

Today we know that string theory gives us general relativity + small corrections. In essence this is because the spectra of closed string theory contains a spin-2 boson, via rather general arguments we know that this has to be the graviton and the field equations are essentially the Einstein field equations. (Remember this is all in perturbation theory).

Recovering general relativity from loop quantum gravity has yet to be done. This I would say is a sticking point right now.

In short, any full quantum theory of gravity must reproduce the phenomena of general relativity is some classical limit(s).