Saw this link on Kottke, described as “How to avoid an untimely death,” with the teaser quote

10. If anyone tries to force you into your car or car trunk at gun point, don’t cooperate. Fight and scream all you can even if you risk getting shot in the parking lot. If you get in the car, you will most likely die (or worse).

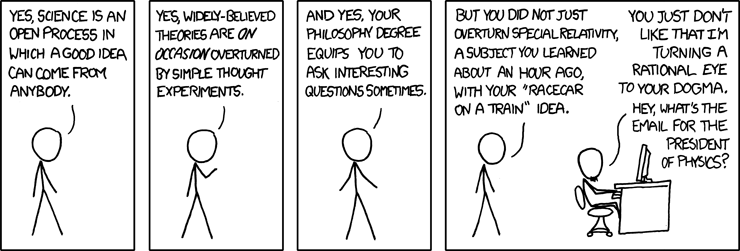

That sounds like the kind of esoteric crap I like reading, so I clicked on the link to the “Dirty Dozen for Black Swan Avoidance” and boy, was I disappointed. I was expecting a list of some unusual events (some kind of event much more common in a TV or movie plot), with tips for increasing your survival probability, along with a physical or statistical justification. I can easily believe that in the unlikely even that someone is forced into a trunk at gunpoint, that their survival probability is low, and that fighting back is the best option. But there’s nothing cited to back that up.

And the rest of the list is worse. On why you should drive the biggest car you can afford:

Despite all the data from the government on crash test safety, I can say unequivocally that in a 2-car accident, the person in the larger car always fairs better. Force=Mass x Acceleration. The vehicle with larger mass imparts the greater force.

So the claim here is that the NTSB data are wrong? Or to be flat-out ignored? (deja vu) And the physics certainly is. The author seems to have failed physics 101 or forgotten Newton’s Third Law — the forces in a two-body collision are precisely the same magnitude; the reason the person in the lighter car is more at risk in a collision is that they will experience a greater acceleration during that collision. But the author has implicitly assumed that there is only risk from a particular kind of collision, and that there are no mitigating advantages to a smaller car. Cherry-picking your scenario is not science. The same kind of logical fallacy lies behind some people’s justification for not using seatbelts (though the author, thankfully, does not advocate this) — that there are scenarios in which not being restrained will help you survive, but this fails to acknowledge that these are a small minority of all accidents, and that the odds are much greater that wearing a seatbelt will help you, should you be in an accident.

Declaring that you don’t believe in global warming isn’t going to score any science points, and this is kind of scary:

If your gas grill won’t start….walk away. Never throw gas (or other accelerant) on a fire.

Ummm, gas grills use propane, so I hope the two sentences aren’t related, as they appear to be (to me). I heartily endorse not putting gasoline on any kind of fire, but is there some epidemic of people putting gasoline on propane grills? If your propane grill doesn’t start, leave some time for the gas to disperse; propane is heavier-than-air and will “pool up” in the grill and/or area below it, and you’ll get a nice fireball when it finally ignites.

Much of the rest of the list is either obvious or based on anecdotal data, without much justification, even if the advice might end up being sound. But without analysis, there’s no way to tell if dying from the stress of building your retirement home is greater than the risk of dropping dead from shoveling snow.