Catching up with blogs after Thanksgiving travel. I saw this on Chad’s linked list. Zen Moments: My Favorite Liar

What made Dr. K memorable was a gimmick he employed that began with his introduction at the beginning of his first class:

“Now I know some of you have already heard of me, but for the benefit of those who are unfamiliar, let me explain how I teach. Between today until the class right before finals, it is my intention to work into each of my lectures … one lie. Your job, as students, among other things, is to try and catch me in the Lie of the Day.”

And thus began our ten-week course.

I think that’s a pretty interesting way to engage the students.

Later on, the author lists some lessons learned from the exercise, including

“Experts” can be wrong, and say things that sound right – so build a habit of evaluating new information and check it against things you already accept as fact.

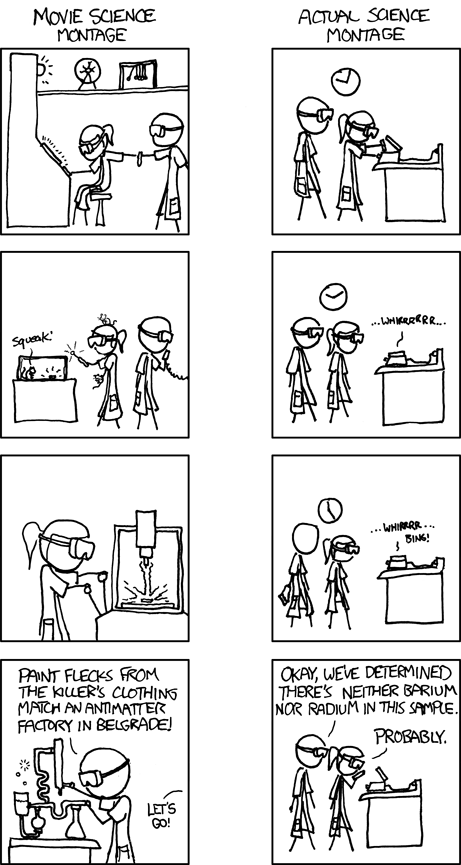

It should probably go without saying, but this holds true for nonexperts, only moreso. Skepticism is a tool that gets refined as one progresses in science, and one tends to develop a decent BS detector. For claims that jibe with what I already know, provisional acceptance is easier. If an assertion seems dubious, I require more convincing. I like Feynman’s trick (can I use that word, in light of the recent kerfuffle?) which he explains in one of his books, of thinking of an object or scenario, trying to disprove an assertion.